Now I want to say right out of the gate that my title probably overstates the case. One new load for an old cartridge probably does not constitute a “rebirth.” But there is deeper water here so hang on while I dip my big toe in the fascinating stream of American firearms history, usage, and marketing.

Savage does not always get credit for being the historically innovative company that it has been. The .300 Savage was introduced in their great Model 99 lever action rifle in 1921. That is over 90 years ago, math fans. Savage wanted a cartridge that would scoot a 150-grain bullet at about the same speed as the .30-06, but it had to be much shorter than the .30-06 if it were to work in the Model 99. Their new round filled the bill pretty well in 1921, but as new powder and bullets came along, the larger case capacity of the ’06 put the Savage in the shade. The good, big cartridge will beat the good, little cartridge every time. In the meantime, however, Savage sold a gazillion Model 99s and they and others chambered bolt actions, pumps, and autoloaders for the short three-hundred.

The Original .300 Savage

Over the years, one of the recurring themes in American sporting arms is the idea of a short cartridge being used in a short-action rifle. Rifle folks, including the military, just seem to like the idea of a compact rifle action, but they don’t want to sacrifice power to get it. The .308 Winchester really filled the bill when it came on the sporting scene in the 1950s, and more recently there has been an orgy of short cartridges, short magnums and even Super Short magnums in .30 and other calibers. Many rifles have been chambered for these, but details of how these have done in the marketplace I do not have. It seems that the .300 Winchester Short Magnum may be the most popular of the crop.

The .300 Savage, however, predates the .308 Winchester by thirty years, and it does its work in a case only 1.87 inches long, and a COL of 2.6 inches. Eagle eyes will quickly note that the neck is very short, and that is what you naturally get when you make the body of the case large enough to pack some powder punch, while keeping overall length down. And along with that goes a rather sharp shoulder (30 deg.). The first pic shows the .300 Savage with a couple of sporting rounds of twentieth century

military origin. The short-necked .223 Remington looks like it could be a .300 Savage if it fattened up a bit. Note that the .308 Winchester has almost the same body but is a bit longer in the shoulder and neck. The combination of a straight case with a sharp shoulder and a short neck gives the Savage a modern appearance, and these factors also facilitate accurate headspacing and reliable extraction in a lever action rifle. All of this, folks, was real innovation. The 92-year-old .300 Savage is the archetypal short-action cartridge.

The combination of good performance on medium game (Ref. 1) and a large number of rifles so chambered has kept the .300 Savage in the viable category among purveyors of factory ammo and components. The 150-grain load at a velocity of 2600-2700 fps has been most popular, but a 180-grain load has also been commonly available. The heavier bullet is hampered by a marginal velocity of around 2300 fps. An advantage has been that these loads can use spire point bullets because the Model 99 rifle has a rotary magazine, rather than the tubular type found on other lever rifles. Downrange performance of the Savage is therefore enhanced in comparison with rifles that must use cartridges with round or flat noses. Higher muzzle velocity and better velocity retention both help to put the .300 way ahead of the always-popular .30-30.

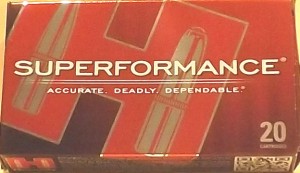

Superformance

A few years ago Hornady updated the lever action scene with the LEVERevolution (Ref. 2) line of cartridges that offered higher velocity and safety in a tubular magazine for the .30-30 and other calibers.

A few years ago Hornady updated the lever action scene with the LEVERevolution (Ref. 2) line of cartridges that offered higher velocity and safety in a tubular magazine for the .30-30 and other calibers.

Hornady’s Superformance line of ammo is different, but it also gets enhanced velocity largely from improved powder technology, which Hornady has pursued with the Hodgdon Powder Company. This line, which yields 100-200 fps additional

velocity, runs the gamut of varmint, big game, and target cartridges in many calibers. I was very happy to see that a Superformance version of the .300 Savage was recently introduced, one which uses their 150-grain SST bullet, a boattail design having a ballistic coefficient of 0.415. The next pic shows three 150-grain, .300 cartridges with the Superformance on the right. Note the red polymer tip of that bullet. Pulling a bullet revealed a charge of 44.7 grains of dark, silver gray ball powder with flattened grains that appeared to be identical with Hodgdon Superformance Powder, a reasonable assumption, but of course we must not identify powder by visual comparison. It also strongly resembles H414. Have a look at the components in the picture.

OK, maybe it is not a rebirth of this old round, considered obsolescent since its replacement by the .308 Winchester, but at least one innovative ammo company feels that it is worth the development of a new load in their premier line. That is a support which a totally obsolescent cartridge would not get. Believe me, the company would not do it if they did not expect it to be profitable.

OK, maybe it is not a rebirth of this old round, considered obsolescent since its replacement by the .308 Winchester, but at least one innovative ammo company feels that it is worth the development of a new load in their premier line. That is a support which a totally obsolescent cartridge would not get. Believe me, the company would not do it if they did not expect it to be profitable.

At the Range

I testfired the .300 Savage ammo in a bolt-action, Remington Model 722. What? No Savage Model 99? Well, no, I do not have the pleasure of owning one of those (yet). The Model 722 was introduced in 1948 and was chambered for the .300 Savage from 1948 to 1959. This Remington model lasted until the introduction of the Model 700 in 1962. My 50-some year old edition is in very good condition with a perfect bore. I do like the 24-inch barrel of the 722; it should be able to take good advantage of the progressive Superformance powder.

Velocity

I used Winchester and Remington 150-grain loads for velocity comparison using a ProChrono unit, with results as follows:

Winchester Super-X 150-grain Power Point: Average velocity, 2657 fps

Extreme Spread, 48 fps; Standard Deviation 18 fps.

Remington Core-Lokt 150-grain PSP: Average velocity, 2622 fps

Extreme Spread, 92 fps; Standard Deviation, 30 fps.

Hornady Superformance 150-grain SST: Average velocity, 2752 fps

Extreme spread, 92 fps; Standard Deviation 28 fps.

Each average is based on at least eight shots. The results would indicate that Winchester and Remington are juicing their loads right up to conventional pressure specs, and, yes, the Superformance does deliver additional velocity. In the case of the Winchester, +95 fps, and +130 fps over the Remington. This happens without exceeding SAAMI pressure recommendations for the cartridge. One could argue about the practical difference in field performance resulting from the velocity difference, but the difference is there, and the very efficient SST bullet will insure that the velocity difference is at least as great out at 200 yards where the deer might be standing.

Accuracy

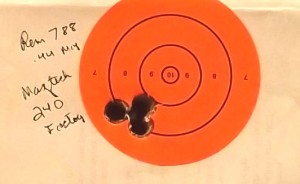

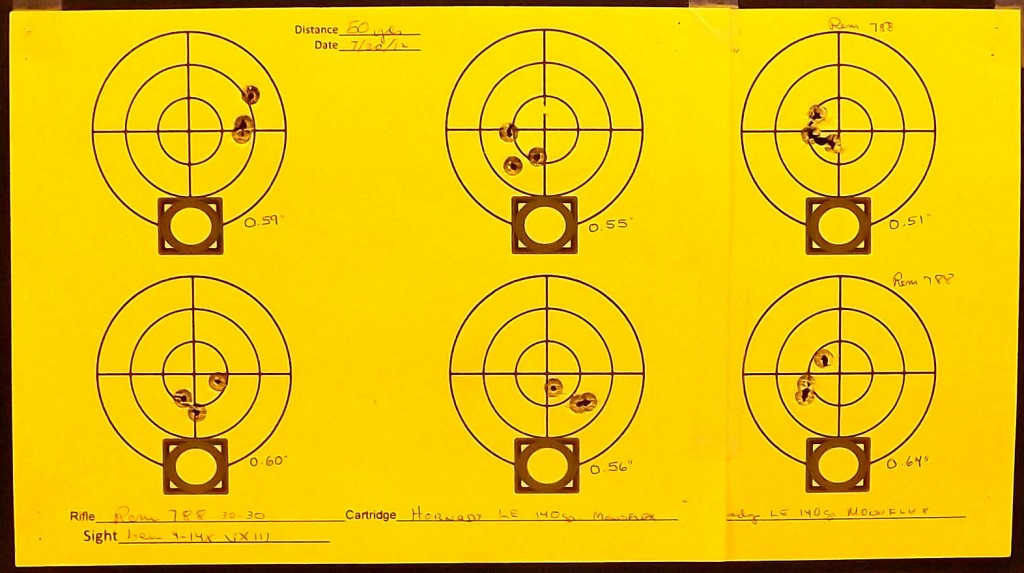

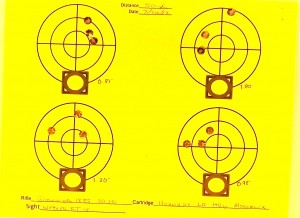

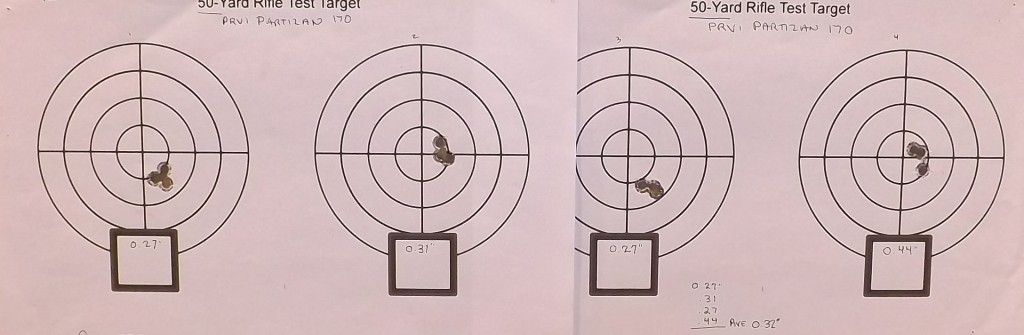

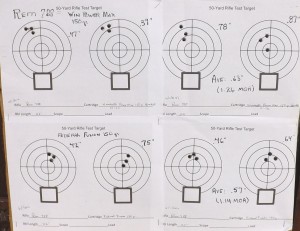

My evaluation of accuracy was not extensive. The Remington 722 is fairly new to me and has yet had no accuracy tweaking. Three, 3-shot groups fired at 50 yards with Superformance ammo averaged 0.90” (1.8 Minute-of-Angle). The smallest of the three groups measured an impressive 0.36”, which demonstrated the possibility for excellent accuracy. The small number of groups fired did not indicate that the Superformance was more accurate than the Winchester or Remington loads; they gave comparable results. More shooting would be needed for a better determination here.

Handloading Possibilities

No handloading yet, but I will find out how it goes in the fullness of time. In his Pet Loads article on the .300 Savage, Ken Waters (Ref. 3) stated that some experts find the round to be a difficult reloading proposition. This might be on account of the short neck, which requires that heavier bullets protrude into the powder space, but Ken found no significant difficulties with the cartridge in his work. The short neck, itself, should present no real problems with good dies and careful technique. On the other hand, the straight case and the sharp shoulder should minimize problems due to lengthening and case life.

Reloading manuals indicate good potential for the cartridge using the lighter bullets. The Hornady Handbook of Cartridge Reloading (Ref. 4) shows 150-grain bullets being boosted to 2700 fps with several different powders and 2800 fps with 44.0 grains of IMR 4064. Then there is the question of what will happen with Hodgdon Superformance powder, which is now available to reloaders. I have found no loading data for that powder in the .300 Savage.

Future Fun

I am wondering just how accurate the .300 Savage can be in a good, bolt-action rifle, so I will be doing a lot more shooting for accuracy with the Remington Model 722 with factory loads and handloads. I promise that I will find out just how good this gun/ammo combination can be made to shoot and I will report the results to you. I caution that the leaves are all down here at ATOTT headquarters, and I do not know how many good range days remain this year. Therefore, there might be lilacs blooming again before you see the full results. However, there is lots of other good stuff to write about, so check out the site from time to time.

- See, for example, Harvey T. Pennington, “All You Need is a .300 Savage,” The Gun Digest 2009, Gun Digest Books, Iola, WI 2008. p. 14

2. See my article “Hornady’s LEVERevolution” at this site.

3. Ken Waters, “Pet Loads for the .300 Savage,” Ken Waters’ Pet Loads, 6th Edn., Wolfe Publishing Co., Inc. Prescott, Arizona 1998. p. 281

4. 8th Edition, Hornady Manufacturing Co., Grand Island, Nebraska, 2010. p. 471

![100246241-1-L[1]](https://ataleoftwothirties.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/100246241-1-L1-300x137.jpg)

![zoom_308MXLR[1]](https://ataleoftwothirties.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/zoom_308MXLR1-300x93.jpg)

![100214835-1-L[1]](https://ataleoftwothirties.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/100214835-1-L1-300x74.jpg)

![BLR-Lightweight-81-MID-034006-m[1]](https://ataleoftwothirties.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/BLR-Lightweight-81-MID-034006-m1-300x78.jpg)

![A5-Hunter-MID-011800-m[1]](https://ataleoftwothirties.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/A5-Hunter-MID-011800-m1-300x59.jpg)

![800px-Browning_Auto-5_20g_Mag[1]](https://ataleoftwothirties.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/800px-Browning_Auto-5_20g_Mag1-300x57.jpg)