The title arm was first described in my blog post of November 11, 2011. When one finds an obscure rifle like this old pole, there has to be some reason for not just ignoring it and moving on. It appeared about 10 years before the Winchester Model 70 was born. And why bother with a gun that only sold in the amount of 6000 copies and was discontinued 70 years ago? Well, what caught my eye with the Super Sporter, in addition to its .30-06 chambering and its appearance at the dawn of the golden age of American bolt-action rifles, was its robust, cylindrical receiver. For accuracy in a bolt action, one wants a very rigid receiver because this promotes the shot-to-shot uniformity that fine accuracy requires. Those shooters who compete in

Receiver of Savage Model 45, Minus Bolt

the bench rest shooting sport know this well and often go so far as to bond additional tubular sleeves to the basic actions of their match rifles to stiffen them and gain another smidgeon of decrease in group size. The Model 45 looked like a winner in the rigidity area, but it would, of course, also need a good barrel and chamber to perform well. These features seemed to be in attendance, so I thought it would be fun to see if this hunch held up during a course of shooting with good glass.

I spent some time during the winter of 2012 working to improve the miserable bedding of the action in the stock. Some work with rasps, carving tools and a Dremel,

Stock inlet after bedding

followed by several goo sessions with Acraglas Gel provided a good, level base for the action. The key areas, as always, were the tang and the area behind the recoil lug inlet. Also, the barrel was bedded for about three inches in front of the recoil lug. The end of the forearm was relieved to float the barrel. This work also resulted in a good channel for the safety lever band and operation of the safety became very positive.

Super Sporter with Bushnell Scopechief

I was delighted to find that I had a pair of Weaver Scope bases which fit the receiver and could be used with the taps that some previous owner had put in. I attached a Bushnell Scopechief 6-20X scope, more scope than one would use for hunting, but great for bench shooting of groups.

A feeling of anticipation keeps you going on a project and keeps you hoping to be rewarded for diligent work. It doesn’t always work out, we know, but when it does, you want to stay in the game.

What to expect? Well, I always strive for one MOA, that is, .5-inch groups at 50 yards or 1.0-inch groups at 100 yards. This, and smaller, is often attained with modern rifles right out of the box but it is a challenge for an old rifle that has needed some work.

The Savage Model 45 At the Range

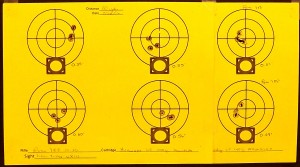

I started with factory loads by Remington and Winchester. These were 180-grain soft point hunting loads. With the .30-06, you have your choice of 125-, 150-, 165-, 180-grain bullets, and heavier, up to 220 grains, in readily-available factory ammo. I think 180-grain bullets are always a good bet in the .30-06, so, not having enough time or money to fire all available bullet weights, I chose the 180s. These factory rounds chronographed in the 2600s.

Five 4-shot groups each at fifty yards averaged .95” with the Remington ammo and 1.19” with the Winchester. Flirting with 2 MOA performance did not seem very exciting, but there is more to it. The groups were nearly all of the three-and-a-flyer type, which indicated to me that the rifle wanted to shoot well, but was just not quite there yet. Measuring the best three out of four in each group gave an average of .89” for the Remingtons and .48” for the Winchesters, the latter (.96 MOA!) being very encouraging.

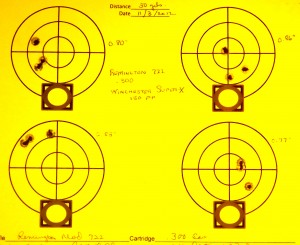

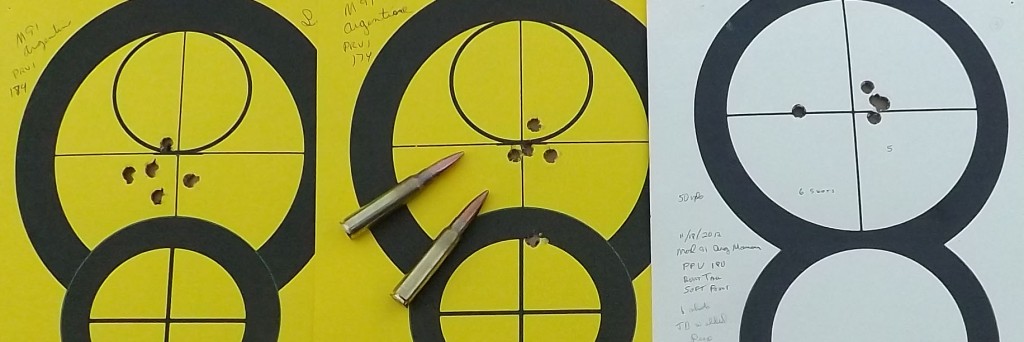

One thing often observed with a newly-bedded rifle is that it does not immediately do its best. It may take 30-40 rounds to get the action settled and comfortable in its new home. I like to loosen and resnug the action screws every 10-15 rounds to help this process along. After firing the factory loads described above, I tried some Prvi Partizan 165-grain soft point loads. I have had pretty good luck with PPU ammo in the past, and the best three groups with these pills averaged .77” (1.54 MOA). Good performance that showed less tendency to produce flyers. Thus, the Model 45 seemed to be settling in.

Handload Happiness

Apart from the cost savings, I stay in the handloading game because a rifle’s best performance often requires some tailoring in regard to case preparation, powder choice, charge weight, and bullet design. Improvement over factory ammo is still possible, if perhaps harder to come by than it used to be. In this case, I felt that the factory load performance had not rewarded my tuning work on the rifle.

The .30-06 can take advantage of progressive powders, that is, powders ranked toward the slower end of the scale of burn rate. Here we would find the 4350s and 4831s under the IMR or Hodgdon labels. Appropriate ball powders would include Winchester 760 and Hodgdon H414. There are many others. Keep in mind that bullet weight is a factor when making a specific choice of powder.

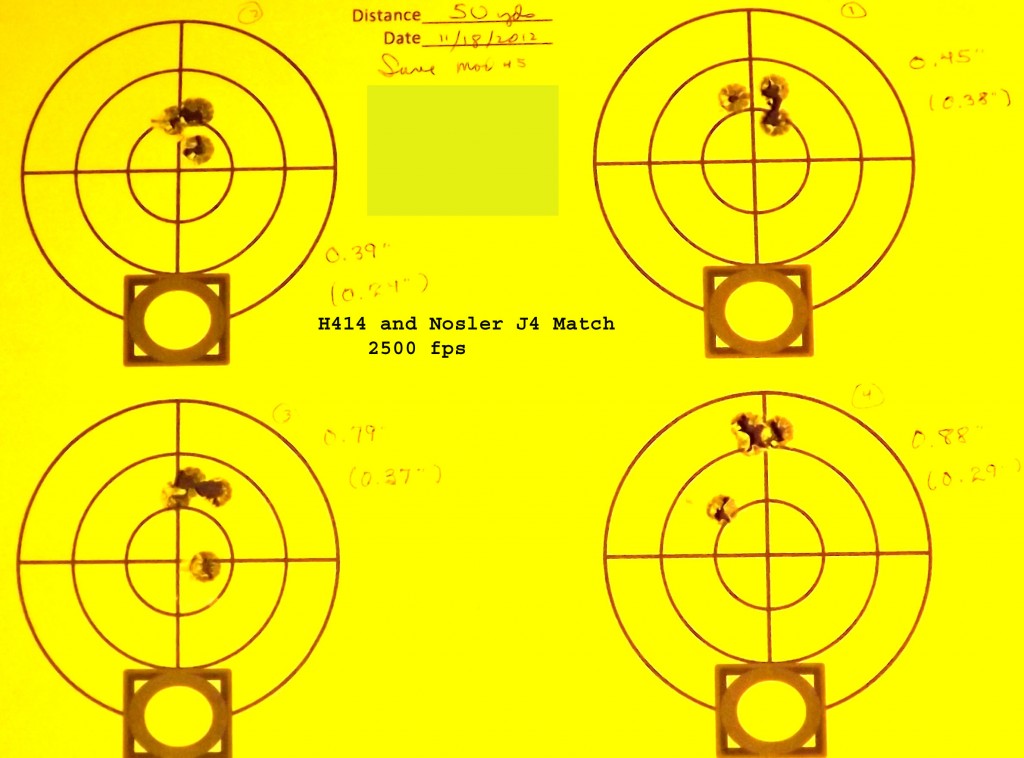

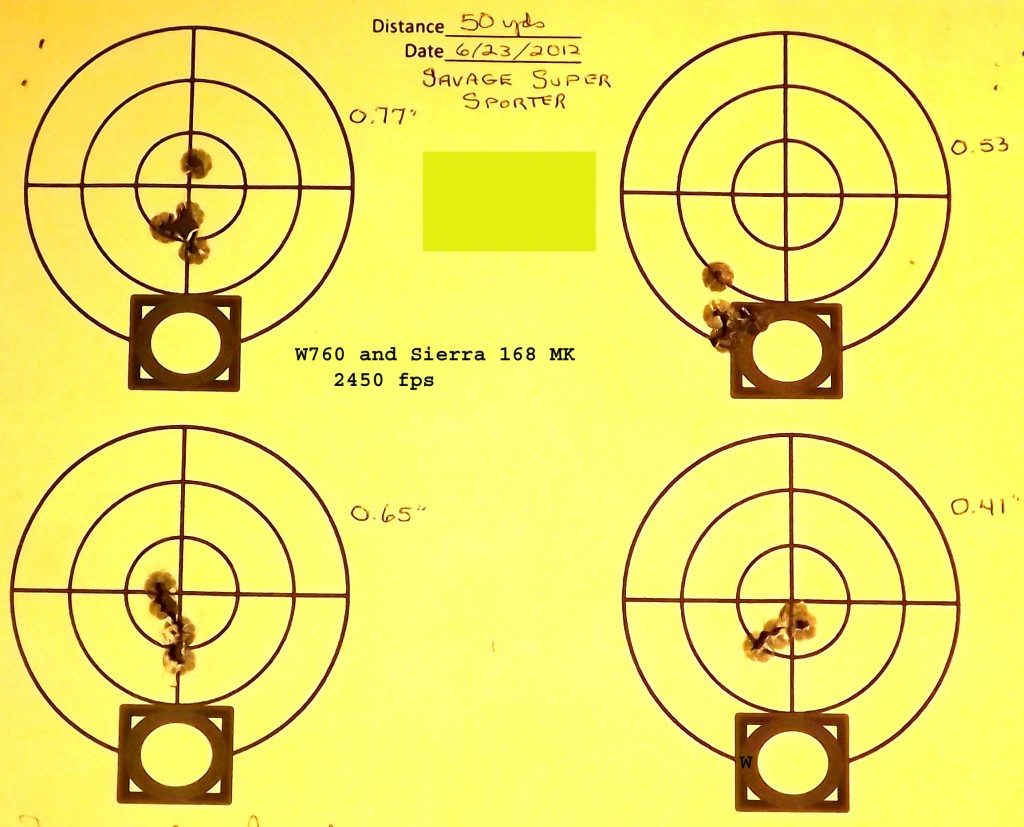

I chose to begin with W760 and bullets in the 165 – 180-grain weight range. I am not going to list charge weights. Velocities in the range 2400-2500 fps were used, and these are easily attainable with moderate charge weights. Four-shot groups were fired at a distance of fifty yards. As usual, multiply by two to estimate the 100-yard, or Minute-of-Angle measurement.

Hornady 165 grain SP: Three groups ave 0.60,” with smallest group 0.36.” W760 (Very encouraging)

Sierra 180 grain Flat base SP: Four groups averaged 0.58,” smallest 0.47.” W760 (Still encouraged)

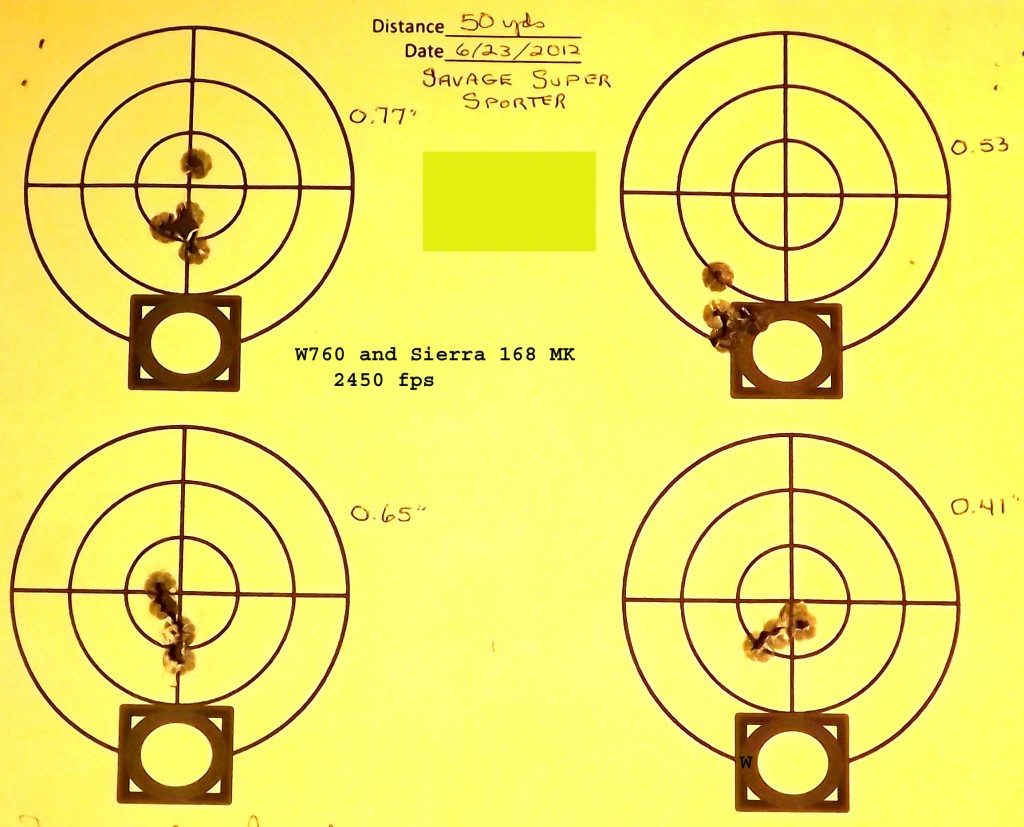

Sierra 168 grain HPBT MatchKing: Seven groups ave 0.50” even, smallest 0.26.” W760 (One minute of angle. O happy day!)

Four Consecutive Groups Using W760 and Sierra MK

Powder change:

Sierra 168 grain HPBT MatchKing: Four groups averaged 0.65,” smallest 0.58.” IMR 4350 (A bit less accurate, but not bad)

Powder and bullet change:

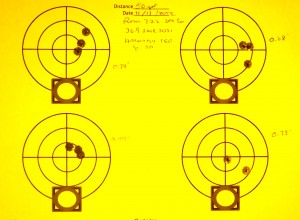

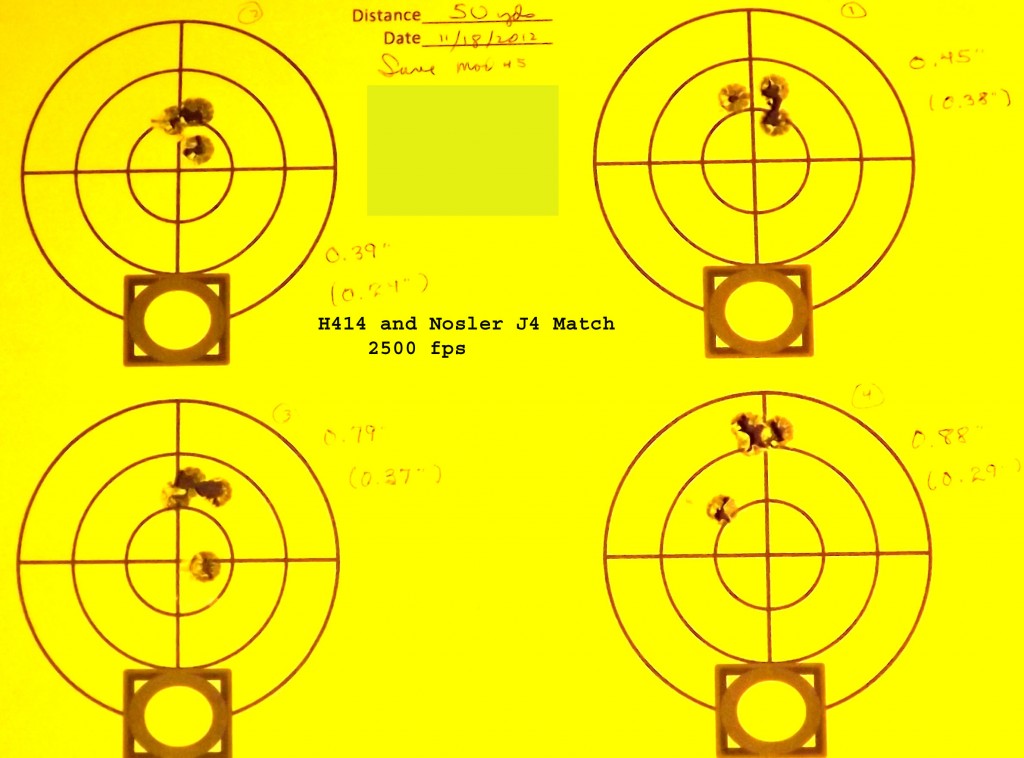

Nosler 168 grain J4 Match: Five groups averaged 0.63,” smallest 0.39.” H414 w. CCI primer (Best three shotgroups averaged 0.32,” ignition erratic)

Four Groups Using H414 and Nosler J4

Nosler 168 grain J4 Match: Four groups averaged 0.50,” smallest 0.31.” H414 w. Remington Magnum Primer (Ignition OK, great groups)

Using Magnum Primers

The gun thus proved capable of groups of 1 minute-of-angle, or a little larger, with several powder-bullet combinations and not a lot of searching for usable powder charges, meaning, the gun is not picky regarding its load. Clearly, the Sierra Match King was the exceptional performer, with twenty groups averaging 0.56” (1.12 MOA). The Nosler match bullet is comparable, but the H414 powder required magnum primers for uniform ignition and avoidance of large velocity variations and group flyers.

Throughout these tests the Model 45 functioned well with positive, but not really smooth, loading and ejection. It was not temperamental in regard to barrel heating, bore fouling, or how it was held in the rest. The trigger had a bit of creep and that may have had a small effect on group performance.

What to Take Away

This project was a lot of fun because it was very satisfying to have my hunch about accuracy work out. That doesn’t always happen. Once again, a vintage rifle is shown to have potential for very good accuracy and careful attention to action bedding allows it to do its best. We should all go out and look for used Savage Model 45s, right? Nah, that would be futile, but if you should happen to run on to one, the price will be right. You might need to do a bit of tuning to make it sing, however.

My loading and shooting of the Super Sporter has actually only scratched the surface, considering all of the available powders and bullets for the thirty caliber. What I did do, however, told me what I wanted to know, so I will be selective in future work with the Model 45. I would like to do some more shooting with the 168 grain match bullets. I have a feeling that pushing them a little harder might be good. Also, I would like to try some cast bullets. The .30-06 is not the best choice for cast bullet shooting, but this gun has a good bore and is inherently accurate, so it could do quite well. So much shooting to do, so little time. Cheerio!