It is universally believed that you must use a good telescopic sight when you want to get the most in accuracy from your rifle. Precision shooting from the bench requires the minimization of aiming error, which will make differences in group sizes due only to differences in the load or the gun, and not to chance fluctuations in sighting conditions. It is impossible to argue against magnification as an aid to precision shooting and, while the sky is the limit on the cost of a scope, there are many reasonably-priced models of good quality. I have used a lot of them, and I love them, but I don’t always like what they do to the appearance and handling of a good-looking rifle. This is especially true of lever actions and single shots. In my book, they just don’t look good with a scope. However, the buckhorn rear sights on the barrels of such arms do not work well for me because, alas, my eyes are no longer young. Luckily, there is a solution.

Precision in the past

Aperture sights, often called “peep” sights, gained wide usage in the nineteenth century. An aperture sight is simply a disc with a small, round hole that is used as a rear sight. The front sight may be a post or a bead. It is a simple matter to look through the hole and center the front sight on the target. Offhand matches at 200 yards were very popular in the 1800’s, and a single-shot rifle equipped with an aperture sight was the weapon of choice. The golden age seems to have occurred near the end of the century when breechloading rifles became common. The apertures were mounted on the tang of the target rifle and were adjustable for windage and elevation. The better sights had Vernier scale adjustments and could be adjusted in increments of 0.01 in., or smaller on the most precise models. On the most popular target, called the Standard American Target, the black bullseye included the eight-, nine-, and ten-rings and had a diameter of 8 inches. The diameter of the 10-ring was 3.36 inches. Over the years, many perfect scores of ten shots were fired, and many strings of tens longer than ten shots were witnessed. That’s right, I said 200 yards. Standing up, shooting offhand with .32-40’s and .38-55’s. These shooters knew what they were doing and they certainly thought they were using precision sighting devices. You can read about it in

Roberts, Major Ned A., and Waters, Kenneth L., The Breech-Loading Single Shot Rifle, Wolfe Publishing Co., Inc., Prescott, Arizona. 1987

Personal Experience

When the Browning Model 1885 “Traditional Hunter” (TH) first appeared, it didn’t take me long to get one ordered in .30-30 Winchester caliber. This rifle, patterned after the Winchester Hi-Wall single shot originally invented by John M. Browning, was made by Miroku in Japan. The model, regrettably, has since disappeared from the Browning lineup. The Quality of the TH is very high, and the gun comes with a tang-mounted aperture sight, similar to an old Lyman or Marble, and a bead front sight. The aperture is about 0.05” in diameter, it is adjustable for windage and elevation, and the front bead is 1/16” in diameter. The sight radius is a long 31 inches! My first trip to the range with the TH was my first serious brush with an aperture sight and I used a Handloader/Rifle Magazine target with a blue border and a white center. Sighting was aided by being able to see the blue border all around the bead in the white. On that day I fired a dozen groups at fifty yards using both factory loads and handloads that averaged less than 1 in. center-to-center for the widest shots. The only group I fired at 100 yds, with a load using Winchester 748 powder behind a Hornady 150-gr. Round-nose bullet, put six shots in 1.4 in. ctc. Shooting at the bench, the peep and bead were easy to bring to bear on the target, gave me a sharp sight picture, and caused no eyestrain in firing over fifty rounds. This was a revelation and I was truly motivated toward more work with aperture sights.

Estimating the Precision of a Peep

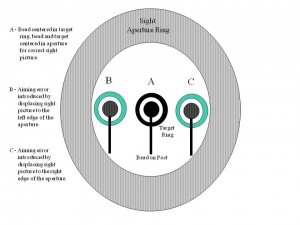

Figure 1 shows three superimposed sight pictures, the correct one in the center, and then left- and right-misaligned sight pictures for an aperture system. Let us try to estimate the maximum error in aiming using the Browning TH parameters for its

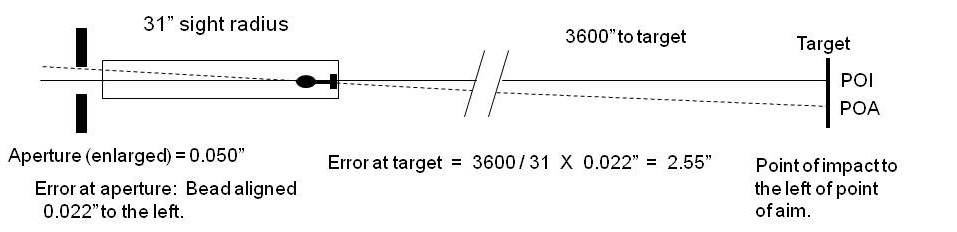

aperture sight. Figure 2 shows a schematic diagram of aperture, barrel, and front bead at a radius of 31 in. in relation to a target at 100 yds. (3600 in.) Assume that the point of impact (POI) of a fired round will lie at the centerline of aperture, bore, and bead, that is, a perfect rifle firing a perfect round. The POI should coincide with the point of aim (POA). Now, suppose we introduce an error in aiming by shifting our aim so that the bead appears at the far left of the aperture field, say, about 0.022 in. to the left of center. This would place the bead near the edge of the .05-in. aperture field. The bullet, however, must still follow the bore axis, that is, the solid line in Figure 2.

Fire a round with this sight picture and the POI will be to the left of the POA. Precisely, calculation shows that the POI will be 2.55 in. to the left of the POA. Of course, one could also err in the opposite direction, or in the up or down directions. This would lead to a maximum group size of 5.10 in., so long as all shots were made with the bead visible in the aperture. The fact is, however, the centering power of the human eye is better than this by a whole bunch. If you have a good rest and reasonably good eyesight, your actual aiming error will be much less than 0.022”. I feel a very conservative estimate would be an error of no more than 1/10 of this amount. That reduces the horizontal displacement of impact to 0.255 in. left or right and predicts a group size of 0.510 in. And with good eyesight and care it could be even better. Precision with a peep is definitely a possibility. Range results of testing this estimation are giving under At the Range below.

Target Design

Realizing the great potential of the aperture-bead system requires a proper target. A proper target will allow one to precisely and easily center the front sight on the POA in a very uniform manner from shot to shot. Target design will depend on the nature of the front sight. With a post or a bead, a six-o’clock hold on a black bull may work fairly well, but, recalling my experience with the blue target described above, I think there is room for improvement.

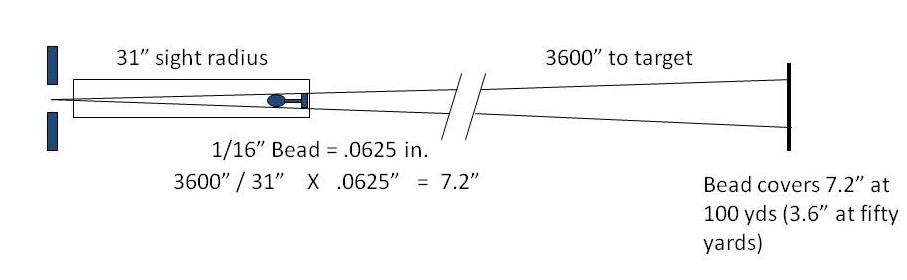

Considering Figure 3, we can see that the angle subtended by a 1/16 in. bead at a 31-inch sighting radius would cover a circle that is 7.2 in. in diameter at 100 yards, and 3.6 in. in diameter at 50 yards. Black bullseyes of these or smaller diameters would be completely covered by the bead at the quoted distances and would not allow precise alignment. To correct this, one needs a bull of larger diameter, so that the bead can be centered in the bull in the sight picture. I reasoned that the bull should be a bright color, because in most light in target situations the bead appears black against the target, and sight black can also be applied to enhance this appearance. The bull diameter should be large enough to give the bead a visible yellow border when centered. Accordingly, I made up a 50-yd target by cutting circular bulls of 5.6-in. diameter out of bright yellow paper. According to the calculations, this would give a yellow border about 1 in. wide around the image of the black front bead in my sight picture. I then pasted a couple of the yellow bulls on a 12 x 18” piece of black construction paper, in effect, giving a black border to the yellow bulls (Fig. 4). For a

100-yd target, the same was done by mounting a 10-inch yellow bull on a piece of black paper.

This kind of target trendously improves aiming precision because it effectively creates an aperture in the target plane. You now have an aperture in the peep before your eye and an aperture in the target plane. The front sight bead is the connection between these apertures, and the eye readily centers the bead in both of them in a very precise and repeatable way.

It should be pointed out that this sighting mode is similar to that of using a globe front sight with a ring insert, which also gives a front aperture that may be centered on a black bull at the target. This is versatile, because one can use different sizes of inserts for different size bulls, and it requires no special target preparation. I prefer the simple bead, however, because it is faster in acquiring a sight picture, it is not as bulky as a globe unit, and I have a more difficult time seeing the front ring of a globe sight in sharp focus.

Now having fired many groups using this target plane aperture method, I can say that it works extremely well. Group sizes are often quite surprising, and the low level of sight error estimated in the previous section can be confirmed by experience. Bright, sunny days are best for good results. For routine work at fifty yards, I have replaced the yellow paper circle on black paper with a black circle of correct diameter printed

by computer on yellow paper (See Fig. 5). If the black circle is a band an inch wide or so, a regular 8.5 x 11” piece of yellow paper will hold a fifty-yd target.

At the Range

Most of my range work was done with the Browning Model 1885 Traditional Hunter having the sight characteristics upon which the above discussion was based. The TH has been an extremely reliable platform for testing .30-30 ammunition. My load of choice was a charge of Winchester 748 behind a Sierra 170-gr. jacketed flat nose bullet. Although I could use any bullet design in the TH, I chose the Sierra .30-30 bullet because it is very accurate and has worked very well in all of my .30-30 rifles. In preparing the test loads I used once-fired Winchester cases, deburred the flash holes, neck-sized with a Lee Collet Die, and trimmed all to uniform length. Bullets were seated with a Forster Bench Rest seating die.

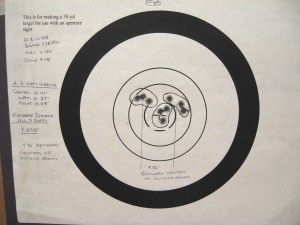

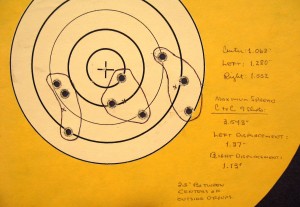

My main shooting interest was to see if I could verify predictions concerning the error in aiming with an aperture sight. To that end, I fired three, 3-shot groups on a single target using the three sight pictures shown in Figure 1, one group centered as well as I could, then one with bead misaligned to the left of the aperture circle, and one with

bead misaligned to the right. Results obtained at fifty yds are shown in Fig. 6 and for 100 yds in Fig. 7. The groups for the three sight conditions are circled, and, while there is some overlap in the fifty-yard trial, the results are about as expected, except that the spread between the error groups came out less than predicted above. The three well-separated groups on the 100-yd target shown in Fig. 7 measure 1.06”, 1.28”, and 1.55”. The centers of the wide groups are approximately 2.5” apart. The results at the two distances correlate well.

Evidently, my aiming error was less than the proposed 0.022”. This is understandable because I held so that the target ring was entirely visible in the aperture field. I have no way of measuring the actual error other than to consult the groups in the figure, which seems to indicate an aiming error roughly half of the value used in the estimation above. But there is a better point to make here. The aperture sight system was good enough that I could get reliable results in support of theory in spite of the age of my eyes. The centers of the wide groups are about 1.2 in. apart indicating that, so long as I could see the bead in the aperture, I really could not shoot a group larger than these nine shots with a gun and ammo of the quality used here. And this while trying to aim badly. Careful sighting to eliminate error would give much smaller groups, of course. Peeps are for Grandpas!

Accuracy Unlimited

Well, perhaps not unlimited, but certainly confidence-inspiring. I could list or show lots of groups, but I will show just two more. The group shown in Fig. 8 (three shots) was fired at fifty yards with a Model 1896 Krag (.30-40) carbine fit with a Williams

FP aperture sight. It measures 0.42 in. CTC. The load used W760 behind a Sierra 180-gr spire-point bullet. The group in Fig. 9 (five shots) was fired at 100 yards with the Browning Model 1885 Traditional Hunter. It measures

0.89 in. CTC. Without the flyer (?) it measures 0.50 in. CTC. The load used W748 powder behind a Sierra 170-gr flat-nose bullet. Shooters have good days and bad days, and, admittedly, these groups were fired on very good days. However, really good groups appear with satisfying regularity when following the practices outlined here.

In addition, shooting a small group while using a peep is just a whole bunch of fun. Switch the front sight to a sharp-pointed post and you can hit yellow-center clay birds at 100 yards. Now and then you might be able to shoot smaller groups than the fellow at the next bench who is sighting in his new, scope-sighted magnum. It has happened.

More Advice

Not many sporting arms have the long sight radius of the Browning TH, and many will have larger front beads. If you wish to make up some targets to try the sighting technique described above, keep in mind that a shorter sight radius and/or larger bead will require a larger circular field on the target area for a good sight picture. This may require some experimentation and I would recommend to start with a 6.5-inch open circle, and have fun.

Conclusions

An aperture sight is effective and preserves the original lines and concept of a vintage rifle. It goes without saying that a peep is good enough for hunting under normal conditions at reasonable ranges. A larger aperture should be used for this, many are available, and the choice of front sight would also be important. A fiber optic type should be good. They are available in 3/32” diameter, which shouldn’t cover up too much fur out to 150 yds or so. Trying one out at the bench is on my to-do list.

The aperture-bead system is precise enough that aiming error can be less of a concern than ammo quality or rifle accuracy performance with sporting rifles. This means that different factory loads and handloads can be compared with some confidence using an aperture and careful bench technique. Obviously, a peep will not be useful for evaluating really small differences in accuracy for bench rest or long range shooters.

On the other hand, how about a little 100-yard benchrest competition with peeps? The 100-yd Hunter Bench Rest scoring bull fits quite nicely in my 5.6-in. yellow bull for work at fifty yards. Put it in a 11-in. yellow bull and you could try it at 100 yards. How about rimfires with peeps shooting for group size or score? Before you holler “Bull-oney,” think about this. You don’t have to see the scoring center sharply. All you need to see is the yellow bull with border. Then, if you are very good at sight adjustment……Hmmmmm.

In the end, I still love scopes and I am still going to use them for certain ammo and rifle evaluations, but peep sights are very precise, great fun, and worthy of wide usage in a variety of shooting activities.