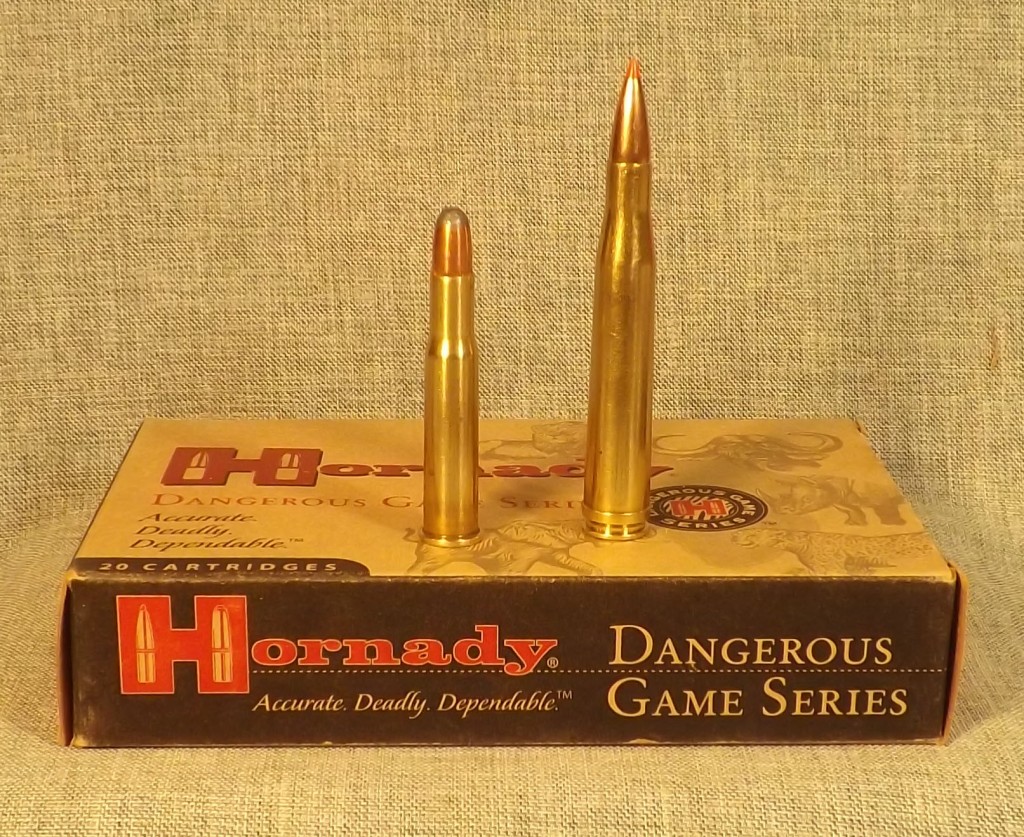

Unlikely! How could these two possibly be related? The first, born in America at the very beginning of the smokeless powder era, a hunting cartridge considered only “adequate” for whitetail deer. The second, born in Britain in 1925, has twice the powder capacity of the .30-30 and so is “adequate” for larger species of American game and a lot of African game. Besides, the .30-30 has a rimmed case and has always lived, well, 95% of the time anyway, in an American lever action rifle. The .300 H&H uses a belted case and has usually been furnished in elegant European bolt actions.

I will admit that they do not sound much like brothers. But wait just a sec, they both fire .308” bullets, so what we have here is

A Tale of Two Thirties.

There is a strong family resemblance in case shape. Both cartridges have tapered case bodies, sloping shoulders, and long necks. Modernists will simply say that this shows their age. In today’s shooting world, straight case bodies, sharp shoulders, and short necks are the rage. The brother thirties are opposite on all counts, but very like each other.

A more important similarity is more subtle. The rim of the .30-30 and the belt of the .300 H&H are two kinds of flanges that position the cartridges for reliable ignition of the primers, making contact of the case shoulder with the chamber shoulder unnecessary. The .30-30 and the .300 H&H are functionally identical in this respect.

Headspace

Headspace is a property of a rifle’s chamber. A simple definition is that headspace is the space that the rifle provides for the cartridge and the fit of the cartridge in that space must be very good. Headspace is a distance that is described in terms of certain measurements of the chamber and the chamber’s relation to the bolt face of the rifle.

For the brothers described here, headspace is the distance from the closed bolt face to the front surface of the flange seat, be it for rim or belt. Either cartridge is thus immobilized when the rim or belt comes against the surface cut for it in the rifle’s chamber, as it is forced forward by the bolt face.

Unlike rimless cartridges, consistent ignition does not require the shoulder of a rimmed or belted cartridge to contact the shoulder of the chamber. If a .30-30 or .300 H&H rifle has correct headspace, it will produce reliable, consistent ignition regardless of the position of the shoulder of the cartridges being fired. This is necessary considering the sloping shoulders of the two cartridges. Rims and belts are identical in the headspacing function, but belts allow cartridges to feed more reliably in repeating rifles.

Another advantage is that the brothers combine this headspacing property with a long cartridge neck, and the resulting bullet friction promotes consistent powder combustion. Reliable, consistent ignition and powder burning are the first requirements of fine accuracy, and the case properties of the .30-30 and the .300 H&H put them ahead of the game in the accuracy search.

Firing Factory Cartridges

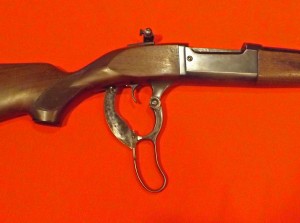

Top: Ruger No. 1S .300 H&H with Burris 6X target scope. Bottom: Browning 1885 Traditional Hunter in .30-30 with Weaver KT-15X target scope

The single-shot rifles shown in the pic above are excellent arms for evaluating the accuracy of factory cartridges. Headspacing on a rim or belt makes the chambered shoulder position of these cartridges less critical than that of a rimless cartridge. If the case body, base to shoulder, is a bit short, firing will simply blow the shoulder forward to fit the chamber. If headspace is correct, there will be no significant lengthening of the case ahead of the rim or belt, and therefore little danger of a case separation. A case can stand quite a bit of this forward expansion without cracking or separating. For proof, just look at what happens when a factory cartridge is fired in an Ackley Improved chamber. This is accepted practice for safely forming AI cases.

Nevertheless, today’s rimmed and belted cartridges seem to be held to exacting tolerances in regard to body length. This can be determined by using a headspace gauge to measure shoulder position before and after firing a factory round. I did this for some .300 H&H cartridges that I fired in a Ruger No. 1S rifle. I used a Hornady Lock’N’Load Headspace

Gauge for this measurement. This tool provides several drilled shoulder bushings that fit on a caliper. The distance from the base of the case to a point on its shoulder can thus be measured, using the appropriate bushing, as shown in the picture. For a rimmed or belted cartridge, note that it is not the actual headspace that is being measured, but the practice does give a reliable measurement for comparing the shoulder position of unfired and fired cases.

Using a 0.400” bushing I obtained the following average values for some .300 H&H loads.

Unfired ammo: Fired cases:

Federal Premium Trophy 180 gr 2.281 in. 2.283 in.

Handload: New Norma Cases 180 gr. 2.271in. 2.280 in.

The Federal factory load pushed the shoulder only .002 in. indicating an extremely good match of cartridge and chamber dimensions. The handload lengthening of 0.009 in. is certainly quite modest.

Handloading

Case resizing is the most important operation in the handloading of the brother cartridges. Firing a case causes the brass to flow forward to a certain degree. Conventional wisdom says that tapered case bodies and sloping shoulders promote this forward flow and will lead to the need for frequent case trimming and shorter reloading life. Full-length resizing will overwork the brass with repeated shortening and lengthening, and that can lead to case separation, a dangerous result.

There is truth in the conventional wisdom, but a certain practice can lead to safe reloading and reasonable case life. My advice here will apply to both the .30-30 and the .300 H&H, as well as to other rimless and belted cartridges.

Avoid full length resizing.

For either cartridge, after first firing the shoulder will have blown forward and the case will fit the chamber well. The case is thus fire-formed in the chamber, and good reloading results can now be obtained with neck sizing, only. I have generally found this to be true when using a Lee Collet Neck Sizing die. This die sizes the neck for good grab without setting the case shoulder back. Brass ahead of the rim or belt is not worked so case life is improved, with case separations becoming less likely. I have had no difficulty in chambering reloaded rounds so sized, although I have had much more experience with the .30-30 than with the .300 H&H. I expect to get much more work done with the magnum this summer.

It is also possible to adjust a full-length resizing die for neck sizing only. This is a trial-and-error process of adjusting the height of the die relative to the shellholder, then running a case, and then taking a measurement. It is OK if the shoulder is set back a thousandth or two. Most loading manuals give detailed instructions for this process.

You can use the Hornady LNL Headspace Gauge for the measurement, but the Wilson Co. also has a nice item for this operation. The picture shows the Wilson Adjustable Case

Gage* for the .300 H&H. It has a shoulder-neck insert that is adjustable and can be locked with allen screws. The insert is set using a once-fired factory case. The insert is locked at the position in which the case head is even with the surface of the groove on the end of the gage, as in the picture. The resizing die is then set so that the shoulder is pushed back to the extent that the case rim falls between the upper and lower surfaces of

the gage groove. This indicates a shoulder push of 0.001 – 0.002,” and gives correct case shoulder position for your rifle with a minimum of strain on the brass.

Note: These methods of sizing require that the reload be fired in the same rifle that produced the fired case. If you wish to produce loads that can be fired in any rifle of the caliber, then you must use full-length resizing.

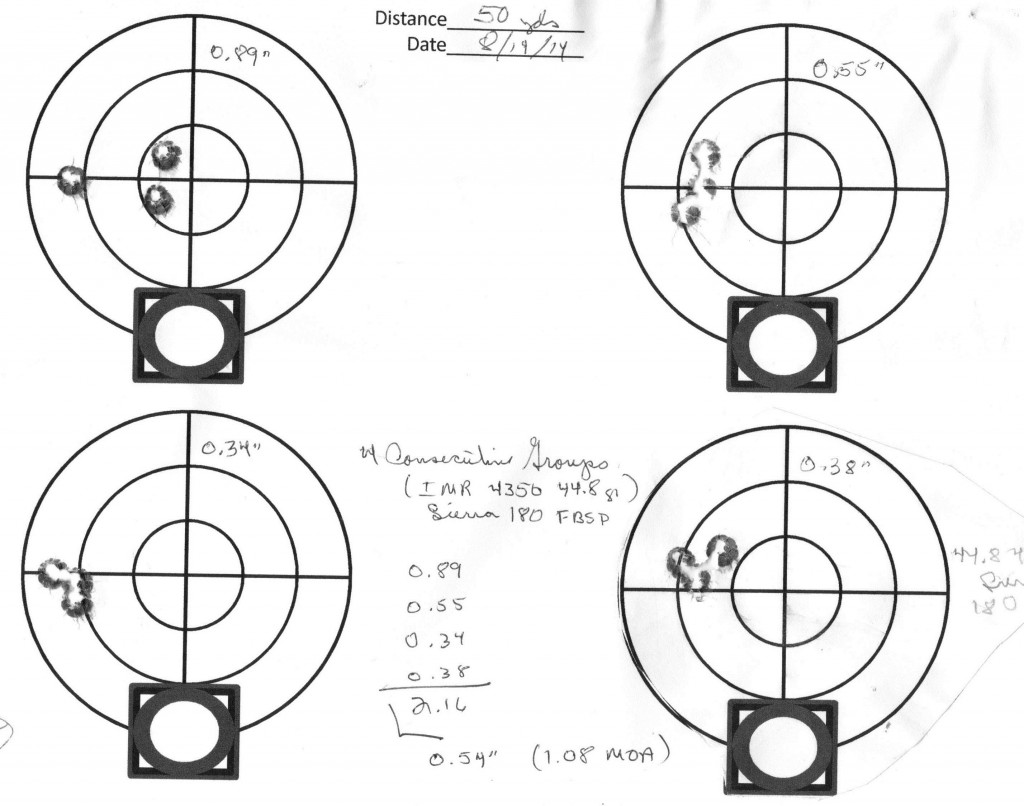

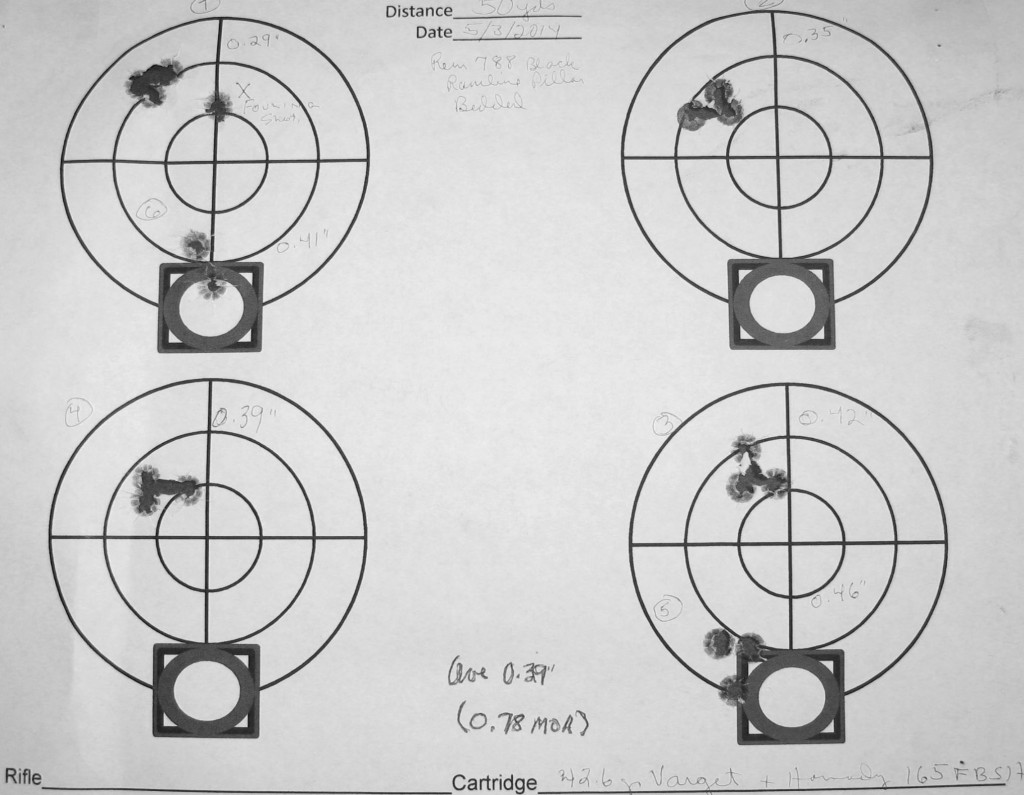

Let’s recap. The rim or belt insures excellent ignition, the long neck promotes efficient powder combustion, and neck sizing gives reloads with a custom chamber fit. Without doing anything special you are on your way to accurate shooting. Get a little more particular with case preparation and it only gets better. Articles on both cartridges have long indicated that they are not finicky when fired in a good rifle, and it is usually not difficult to find a good powder-bullet combination for fine accuracy. This has certainly been my experience with the .30-30, especially in bolt action rifles or single shots. I think the same will occur with the .300 H&H as my experience with it grows. If my bones can take the punishment, I want to find out just how good the Ruger No. 1S/.300 H&H combo can shoot.

Parting Thought

I will leave you with the appealing idea that the brothers in brass also have a little sister. She is the .22 Hornet and she has been around a long time, also. Tapered case body, sloping shoulder, long neck? You bet, so everything expressed above applies.

*The tool is a “gauge,” but Wilson uses “gage,” so I am using their spelling.