Assume that a rifle has a well-cut chamber. The chamber is perfectly aligned with the bore of the rifle and provides a good fit for the cartridge case. A cartridge chambered and waiting for the firing pin constitutes the “initial conditions” of a shot. Shooters believe that a very accurate load will result when initial conditions are very uniform from shot to shot. That is, accuracy is related to initial conditions.

Lest you say “Duh! That’s obvious!” consider this. If there are deviations in initial conditions that degrade accuracy, a vestige of the initial conditions must persist when the bullet has emerged from the muzzle and is on the way to the target. These deviations are not corrected by the bullet passing through, say, 24 inches of precision-rifled bore in a fine target rifle. Why? This has always seemed remarkable to me. I will say more about this later with a possible explanation.

Many reloaders take great pains to achieve uniform initial conditions and the best accuracy with their reloaded ammo. Bench rest competitors are probably the main practitioners of this “precision reloading” process. Most of us don’t want to be as persnickety as the bench rest clan is. However, there are a couple of things which the average, noncompetitive reloader/shooter can do to get the best accuracy for her rifle. These are: 1) Insure cartridge case uniformity, and 2) Minimize bullet runout.

Cartridge cases are uniform when the brass in each is the same thickness all way around, that is, the mass of brass is concentric about the long axis of the case. Commercial brass is quite uniform but there will be some variability. A crude idea can be gained by weighing your empty cases. Variations in weight may indicate variations in concentricity. This is most important with small cases like the .22 Hornet, for which I once found a variation of 8% in the weight of one batch of new cases. For precision work I sort my cases by weight.

Another indication arises from measurement of neck wall thickness. If that value varies it can indicate a lack of concentricity for the entire length of the case. This can be measured and a good case will not exceed 0.001” variation in neck wall thickness around the complete neck cylinder.

Bullet runout is perhaps more deserving of attention. It exists when the long axis of a seated bullet is not coincident with the long axis of the cartridge case. That is, the bullet in the loaded round is cocked in the cartridge case and it will not be perfectly aligned with the rifle’s bore. It then gets off to a bad start when ignition occurs. Bullet runout may be caused by an issue with the sizing die or the seating die, or both (!) Bullet runout is also easily measured but I have not seen a statistically reliable analysis that quantitatively relates the degree of runout to some measure of accuracy. However, I think precision shooters feel that a runout of 0.005” is too much for best accuracy, and a runout of 0.01″ is really bad news. On the other hand it is possible to keep runout down around 0.001” with good reloading tools and technique.

Speaking of good reloading technique the tools needed for insuring the uniformity of initial conditions are readily available to reloaders.

Some tools you may already have are:

An accurate digital scale.

A dial or digital caliper.

A case gauge for your cartridge.

A neck sizing die for your cartridge.

Then, some tools you may like to get are:

A case neck thickness gauge.

A case neck and bullet runout measurement tool.

A match grade bullet seater for your cartridge.

Loading some .30-30 Winchester rounds is a good way for me to illustrate the techniques. I have a very accurate bolt action rifle for testing the accuracy of finished rounds. The .30-30 is economical of reloading components and comfortable to shoot at the range. Most importantly, it responds as well as any cartridge to precision reloading techniques.

I started by sorting cases by weight. I had 36 once-fired Winchester cases that had been used in the rifle I wanted to use for accuracy testing. I arbitrarily separated the lightest 6 and the heaviest 5, leaving 25 cases to proceed. I measured the neck wall thickness of the 25 using the Sinclair tool. All 25 showed a variation of no more than .001” around the circumference midpoint of the neck A couple of the weight culls showed 0.002.”

Next, I used a Lee collet die to neck size the chosen cases. I have had good results with this Lee product. It resizes by squeezing the case neck to a mandrel rod rather than by running

the neck into a cylinder section of the die. This eliminates the need for an expander button on the decapping rod, a feature that often causes neck runout problems. The Lee collet die does not set back the shoulder of the case. If I measure the case with a Wilson .30-30 Case Gage before sizing the rim is a bit higher than the face of the gauge. After sizing with the Lee collet it measures exactly the same. Just a bit long but the case chambers easily and has a very good fit with the chamber.

Then, I loaded the powder charge, 31.5 grains of Winchester 748. I weighed the charges because this is an accuracy test, but since 748 measures so well that might not have been necessary.

Sierra 170-grain flat nose bullets were seated using the Forster Ultra Micrometer seater die shown in the picture. This is a great seater die, supporting case and bullet in excellent alignment and allowing micrometer adjustment of seating depth.

Concentricity of completed rounds was evaluated using an RCBS Case Master. This tool allows a dial indicator button to bear on a spot of your choice, either on the case neck or the bullet. For .30-30 I usually choose a spot on the bullet just before the ogive begins and none of my 25 rounds showed more than 0.001” of bullet runout. I had done my best to insure their uniformity.

I hasten to say that I am no more than average in handiness, but I have a lot of loading experience and I work slowly and methodically for this kind of project. You could get the same results.

So let us go to the range

I used my Remington Model 788 for the accuracy firing. The 788, a bolt action rifle now long discontinued, had a good reputation for accuracy in all of its chamberings, which included the .30-30. Mine has always been superbly accurate, especially after I epoxy bedded the action and floated the barrel. It simply will not throw a flyer and has been my main rifle for evaluating all kinds of factory and handloaded .30-30 ammo. It is equipped with a Leupold VX-3 14X scope.

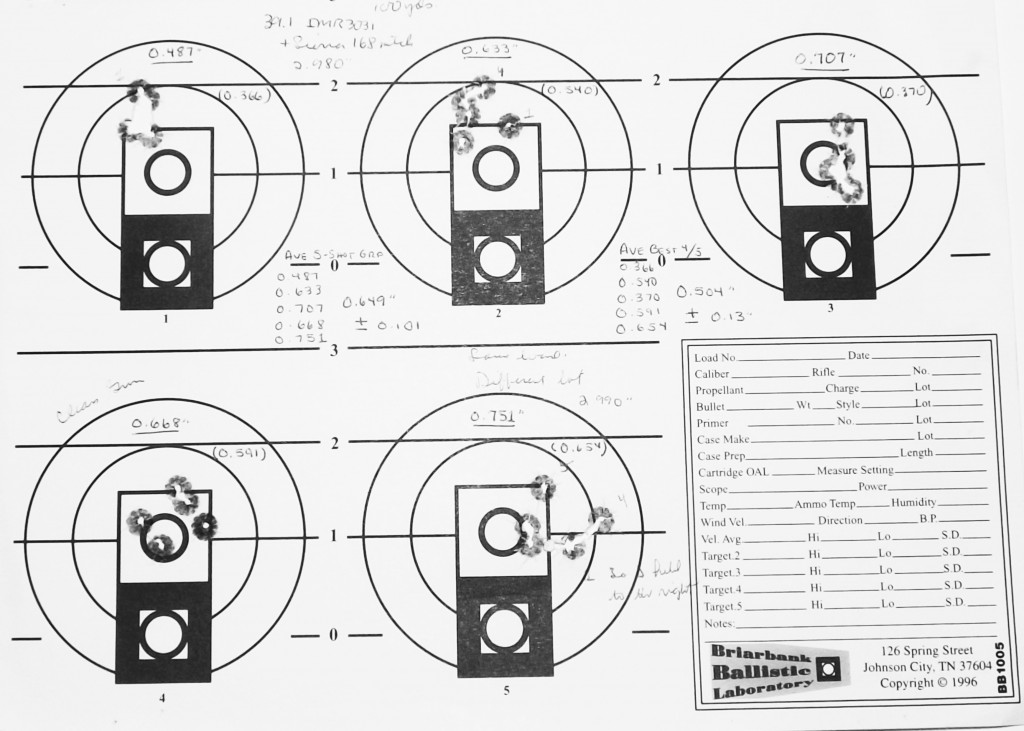

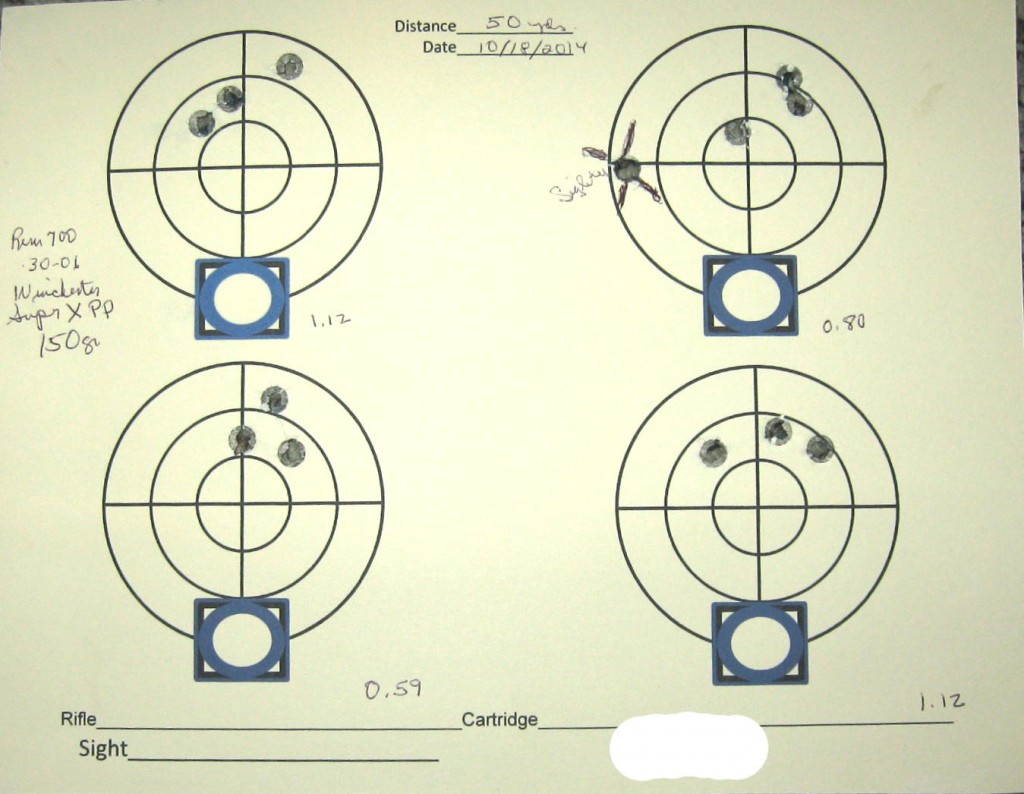

Firing was done with targets set at fifty yards. I used the 25 rounds for one fouling shot followed by 6 consecutive 4-shot groups. Four shot groups are usually good for determining grouping ability and tendency toward flyers. I fired slowly so as to avoid effects of barrel heat.

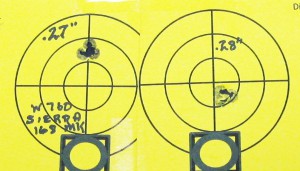

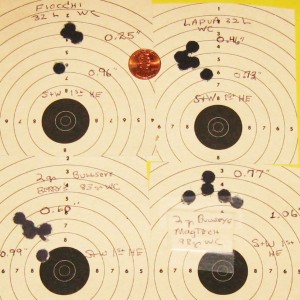

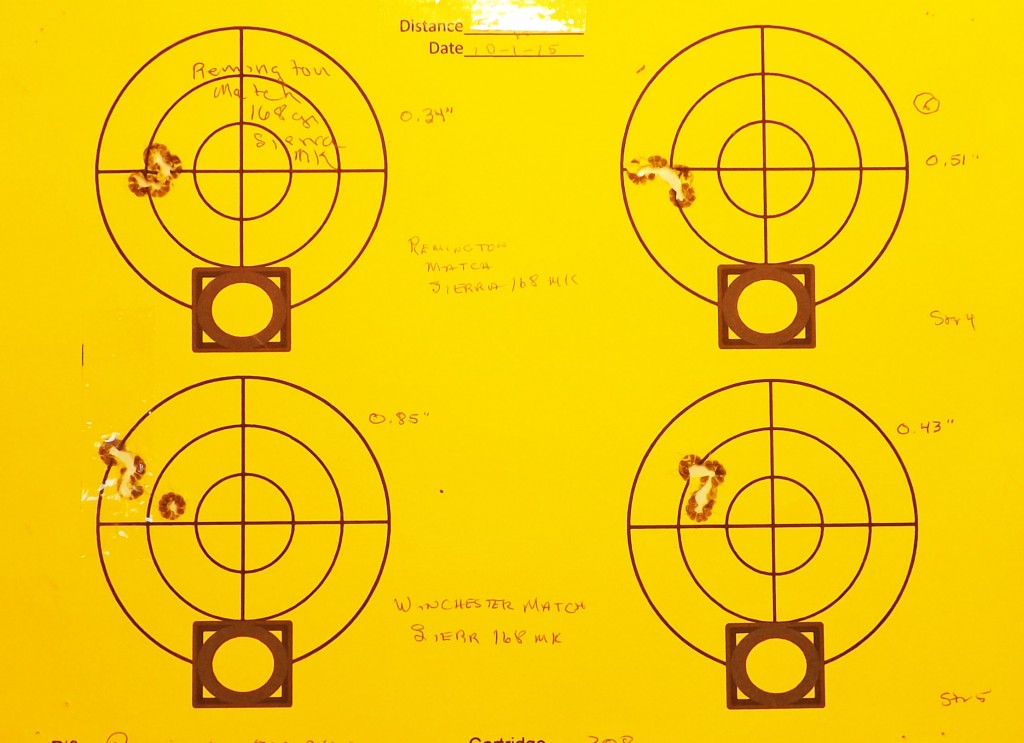

Two groups from the set are shown in the picture. The left one measures 0.44,” the right one 0.16.” That benchrest quality group, remember, has four shots in it. These are two of the best, the largest of the six being 0.98″ and the smallest 0.16.” The average of the six groups was found to be 0.57.” Omitting the largest group gave an average for the best five groups of 0.49″ or 0.98 MOA.

I must say that these are extremely good results considering that:

1) They were obtained using an economy model sporting rifle, well bedded but having no trigger work or action truing.

2) They were obtained using a typical, mass-produced .30-30 hunting bullet, not a target bullet.

3) They were obtained using a cartridge not generally accepted as having superior accuracy.

What shall we conclude about bullet runout?

Can we say that the fine results came from keeping bullet runout very low? Can we say that the results are much better with the measured 0.001″ runout than they would have been with 0.004 or 0.005″ of bullet runout?

I don’t think so.

What we can say is that the loading techniques that I used allowed my good rifle to shoot its best. Low bullet runout made a contribution but there is not enough data here to show a performance difference attributable only to low runout. Along this line we may also point out that one may have a rifle that does not shoot well enough to show a difference in grouping ability with varying bullet runout. And it is likely that some other loading variable, say, overall cartridge length (distance of bullet from lands) may overshadow any variation due to runout. Yes, ammo evaluation should only be attempted with a rifle of proven ability whose response to various cartridge characteristics and loading techniques is very well known.

Personally, I feel that my Model 788 is good enough and that the low bullet runout of my ammo played a good part in this test. Since the layout of time and money is relatively low, it is definitely worth my while to follow the procedures outlined above.

Now tell me, Oh tell me why

variation due to a bit of bullet runout is not corrected by travel through, say, 24 inches of a great barrel in a fine rifle but rather, persists in some way to produce variation at the target.

I suggest that a cocked bullet is damaged by being blown violently forward into the lands when the cartridge is ignited. More specifically, the side of the cocked bullet closer to the bore is abraded so the bullet is then slightly out of balance. Of course, this condition persists after the bullet has left the barrel and it affects the bullet’s flight to the target, ultimately causing larger groups.

This idea may not be original with me but I have not seen it expressed elsewhere. Could have missed it, of course

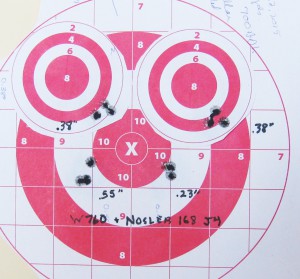

To test this idea I loaded some additional low runout ammo and abraded the ogive of each cartridge with a file. This amounted to a flat strip about 1/16 inch wide on the ogive.

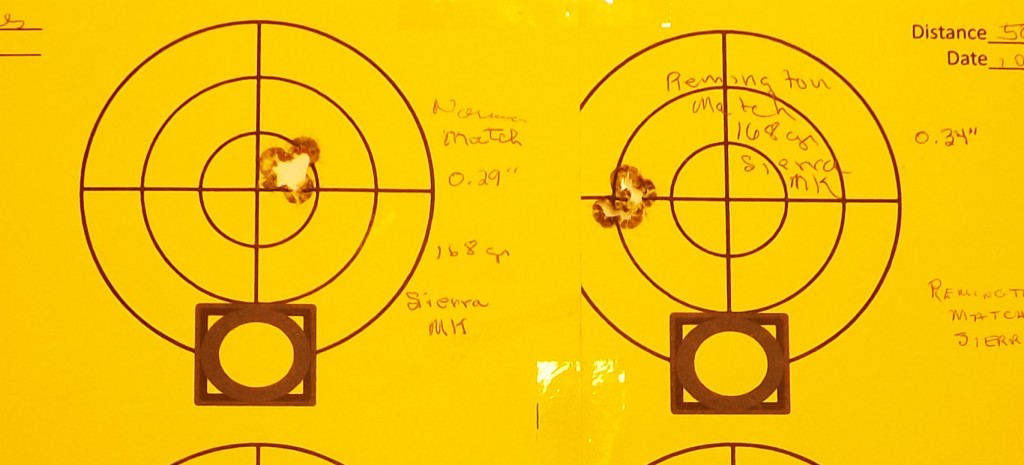

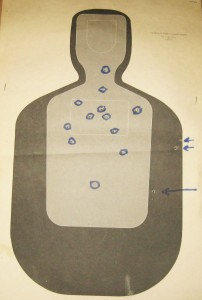

There are a number of reports in the shooting literature of experiments made shootingcartridges with intentionally damaged bullet points. They have often showed little difference in accuracy when compared with undamaged rounds. Firing my abraded rounds also proved inconclusive, that is, too few shots and too little difference in the group. As the picture shows, a six shot group of abraded rounds measured 0.91.” This is smaller than one of the groups in the main series, so, no proof at all that the abrasion made a difference.

Unfortunately, winter has ended my shooting projects for the year and I do not know when I will get back to this question. If you want to abrade some rounds and try them out, let me know the results. In the meantime, I will always use my Lee Collet Sizer and my Forster Ultra Seater for loading my 30-30 rounds.